The concept of biophilic design sits at the intersection of architecture, psychology and ecology. Derived from the Greek words bios (life) and philia (love), biophilia describes humanity’s innate affinity for nature. Harvard biologist E. O. Wilson popularized the biophilia hypothesis in the 1980s, suggesting that our love for living systems is a product of evolution. Biophilic design harnesses this idea by weaving natural patterns, materials and spatial cues into buildings to improve mental and physical health. One of the most influential frameworks underlying this movement is the prospect and refuge theory, which explains why we feel at ease in spaces that provide both openness to see what is ahead and safe places to retreat.

Why our brains crave nature

Humans spent millions of years as hunter‑gatherers on African savannas. Evolution in this context tuned our senses to detect distant threats and opportunities while also locating sheltered spots for rest. Modern neuroscience reveals that navigational networks such as place, grid and border cells map our surroundings and influence how we respond to spaces. These systems, anchored in the hippocampal–entorhinal region, fire when we look across a vista or hide in a nook. Research on the cognitive foundations of urban design notes that the prospect‑refuge hypothesis arose from the savanna hypothesis and that our brains evolved to gauge openness, shelter and complexity for survival. Put simply, our longing for natural patterns and materials is encoded in our neurobiology.

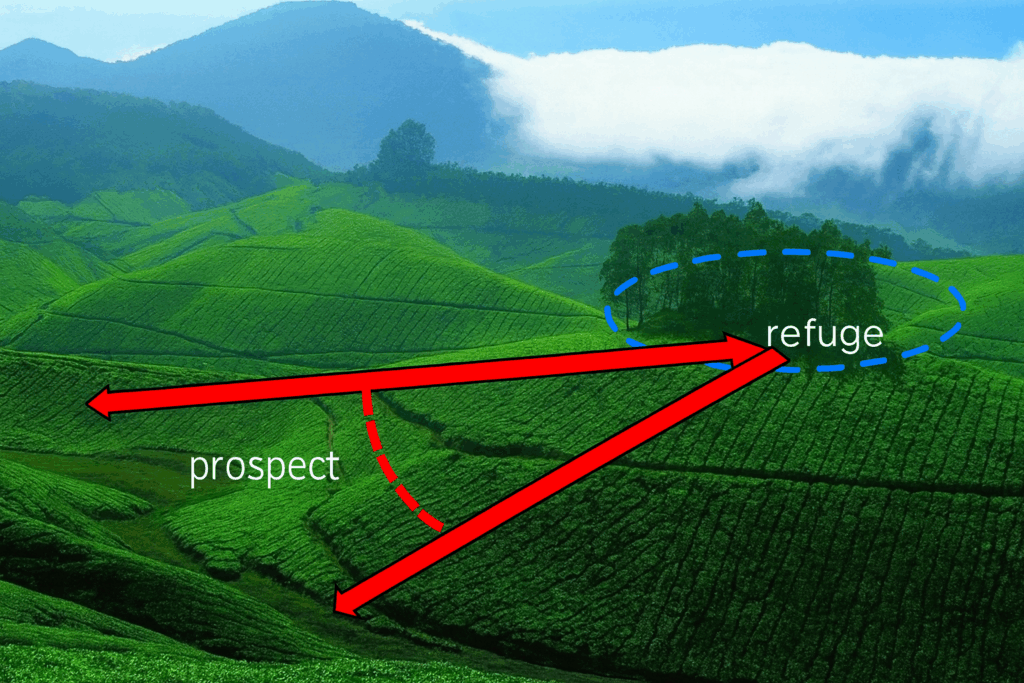

Defining the prospect and refuge theory

British geographer Jay Appleton introduced the prospect and refuge theory in his 1975 work The Experience of Landscape. He argued that humans instinctively prefer environments where they can see without being seen. Over time this idea was expanded by design theorists and incorporated into the broader field of biophilia. Today designers refer not only to prospect (open views) and refuge (protected niches), but also to complementary patterns such as mystery, complexity and risk. Together these concepts provide a toolkit for creating interiors that feel safe yet stimulating.

Prospect: the need to see ahead

The prospect pattern represents an unimpeded view over a distance. Open sightlines give us a sense of control and awareness, reducing stress and boredom. According to Terrapin Bright Green’s influential “14 Patterns of Biophilic Design”, rooms with generous prospects decrease perceived vulnerability and improve comfort. The report recommends creating focal lengths of at least 20 ft (6 m) and limiting partitions to around 42 inches (1 m) so that even seated occupants can see across a space. Open floor plans, elevated platforms, balconies and glass partitions are all practical ways to achieve prospect. Views that include trees, water or other natural elements further enrich the experience.

Refuge: the comfort of shelter

While prospect satisfies our need to survey our surroundings, refuge meets our desire for protection. A refuge space is partially enclosed on three sides and overhead, offering privacy without complete isolation. Terrapin’s research notes that refuges lower heart rate and blood pressure, improve concentration and reduce feelings of vulnerability. Examples range from high‑backed chairs and bay window seats to canopy beds, reading nooks and covered porches. Designers often use lower ceilings, warm materials and softer lighting to accentuate the sense of retreat. Importantly, the best refuges maintain some connection to the larger space so that occupants still feel engaged.

Mystery and complexity: inviting exploration

Beyond seeing and hiding, humans are naturally curious. The mystery pattern involves partially obscured views that hint at more to explore. Environmental psychologists Stephen and Rachel Kaplan emphasise that people need both comprehension and exploration; a hint of what lies beyond sparks fascination and encourages movement. Curving paths, peek‑a‑boo windows, dappled light and filtered sounds all contribute to a sense of mystery. When combined with moderate complexity; variety in forms, textures and materials, mystery sustains our attention without overwhelming us.

Scientific evidence for prospect‑refuge theory

While the prospect and refuge theory aligns with our intuitive preferences, researchers have tested its claims empirically. Multiple studies in environmental psychology, landscape architecture and neuroscience provide support for this framework.

Meta‑analysis of environmental preferences

In 2016, Annemarie Dosen and Michael Ostwald published a comprehensive meta‑analysis of quantitative studies on prospect‑refuge theory. They reviewed research across urban, interior and natural environments and found that open views were consistently associated with higher preference ratings, especially in built settings. Evidence for the importance of refuge was less consistent, though the authors acknowledged that combining prospect with moderate complexity enhanced comfort and interest. The meta‑analysis cautioned that some architectural examples rely on qualitative interpretations, suggesting the need for more controlled experiments.

Field study in a japanese garden

Real‑world evidence comes from a 2018 study of Tokyo’s Hama‑rikyu Gardens. Researchers surveyed visitors at eight different viewpoints and discovered that sites offering both openness and shelter, described as “open‑protected”, were the most preferred. Perceived openness strongly predicted preference, while refuge cues were less distinguishable across sites. Interestingly, the presence of background high‑rise buildings did not significantly affect ratings, highlighting the power of design techniques such as shakkei (borrowed scenery) in creating harmonious prospect‑refuge conditions.

Biophilic interior design can turn your refuge space into a sanctuary that supports mental well-being. The natural elements below aren’t just visually calming, they’re also backed by science for reducing stress and easing anxiety symptoms.

Windows, fenestration and prospect‑refuge

An investigation published in the journal Sustainability explored how window design influences feelings of openness and shelter. The authors argued that fenestration is a critical tool for achieving prospect‑refuge because it allows occupants to see others without being seen. Optimal window dimensions and placements, determined early in the design process, maximise visual access to both indoor and outdoor spaces. They also noted that digital modelling can simulate prospect and refuge conditions, helping architects refine their floorplans.

Neuroscience and cognitive models

Neuroscientific studies complement behavioural research. Investigations into the entorhinal–hippocampal system show that border cells respond to proximity to environmental edges (akin to refuge), while head direction cells fire when our gaze changes orientation (akin to prospect). Though direct neuroimaging evidence is still emerging, preliminary data indicate that natural environments promote functional connectivity between brain regions associated with attention and emotion. This suggests that spaces featuring openness and shelter align with our neural architecture.

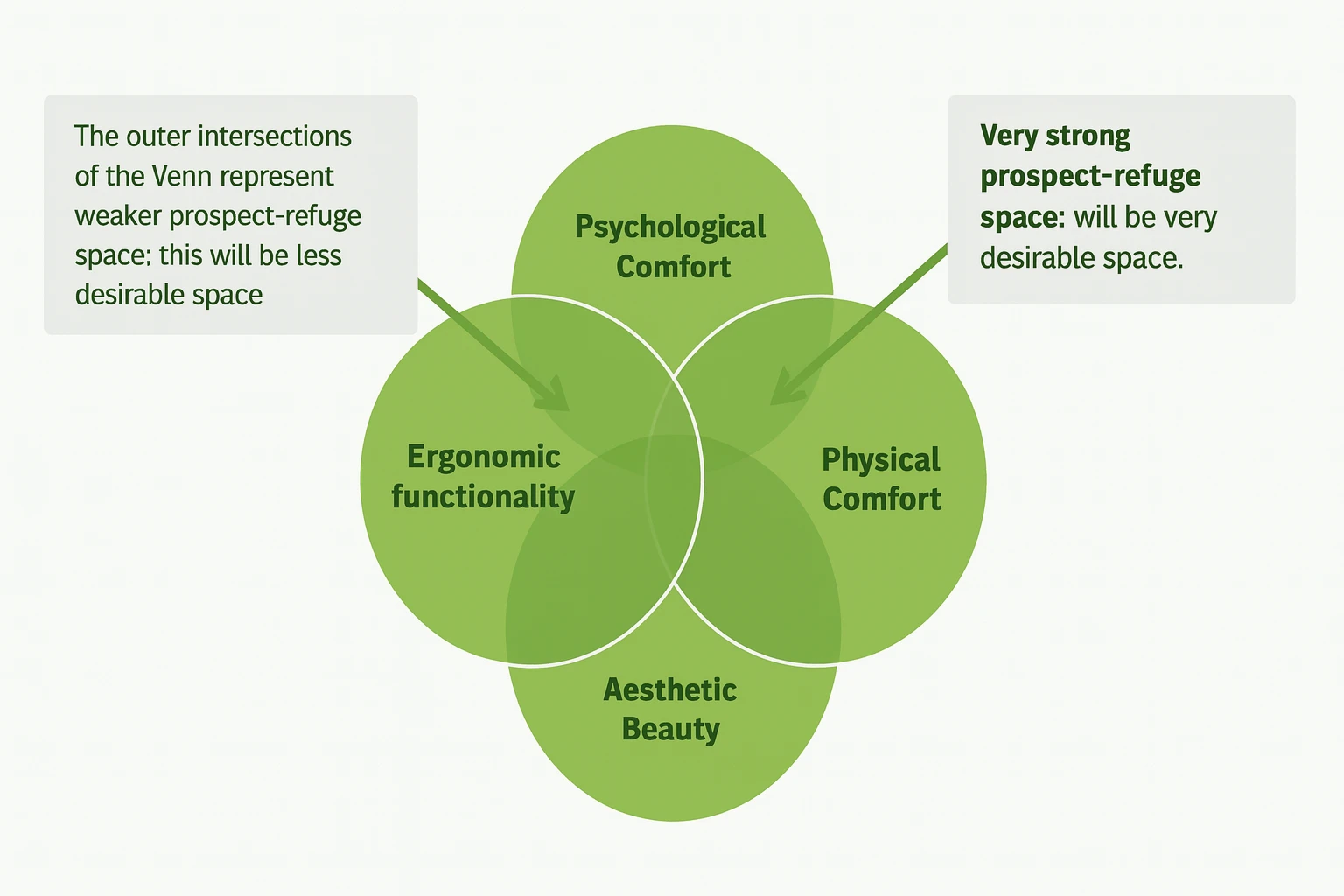

Health benefits of biophilic design

Biophilic design does more than create aesthetically pleasing interiors; it measurably improves mental and physical health. A 2023 systematic review of biophilic workplaces found that access to outdoor environments or well‑designed outdoor areas lowers stress levels. When outdoor exposure isn’t possible, images, videos or virtual simulations of nature still reduce stress. The review underscored the value of multisensory cues, natural sounds, scents and textures, and emphasised shelters and refuges in offices.

Another review on nature exposure during work showed that natural environments decrease blood pressure, heart rate and cortisol levels, while improving mood and cognitive performance. Office workers who spend time in green spaces or environments with plants, natural light and views report greater job satisfaction and lower stress. Even small interventions like indoor plants, window views or nature‑themed artwork yield restorative benefits.

Perhaps the most cited evidence for biophilic design comes from Roger Ulrich’s 1984 hospital study. Ulrich compared gallbladder surgery patients who looked out onto leafy trees with those facing a brick wall. Patients with natural views required less pain medication and were discharged sooner. A 2024 scoping review of hospital environments confirmed that nature exposure reduces length of stay, analgesia use and anxiety. These findings underscore how reconnecting with nature through design can accelerate healing.

Designing interiors with prospect, refuge and mystery

The challenge for architects and homeowners is translating evolutionary principles into floorplans. Fortunately, the prospect‑refuge framework offers practical strategies for interior design.

Maximizing prospect: long sightlines and elevated vantage points

To create prospect, prioritize unobstructed views across rooms or toward the outdoors. Orient seating toward windows, ensure that partitions remain low enough for people to see over them, and incorporate glass balustrades or open shelving to maintain visual connectivity. Elevated platforms, mezzanines and balconies can provide commanding perspectives. When working in dense urban contexts, consider aligning windows across multiple rooms to create internal sightlines. Adding natural focal points such as trees, water features or artwork invites the eye to travel and reduces monotony.

Crafting refuge: sheltered nooks and intimate zones

Refuge spaces offer respite from activity. Carve out alcoves with three sides enclosed and a lowered ceiling. Built‑in window seats, reading niches, high‑backed banquettes and canopy beds are classic examples. In workplaces, small pods or booths allow for private calls and focused tasks. Use warm, sound‑absorbing materials such as wood, wool and acoustic panels to reinforce comfort. Keep a visual or auditory connection to the broader environment so that occupants feel safe yet not isolated.

Infusing mystery: curves, filters and discovery

Introduce mystery by designing paths that curve, screens that filter light and openings that reveal glimpses of what lies beyond. Use plants, latticework or screens to partially obscure views, enticing visitors to explore. Arrange artwork or unique furnishings around corners to reward curiosity. In outdoor settings, meandering pathways and layered plantings create depth and intrigue. Balance is crucial—mystery should invite exploration without causing disorientation.

Finding balance and context

Successful interiors weave prospect, refuge and mystery together. Public areas might emphasise openness and social connection, while adjacent zones provide protected seating. Hallways, staircases and transition spaces can incorporate curves and filters to spark interest. In small apartments or offices, internal windows and transparent partitions maintain sightlines and lighten enclosed rooms. Materials also play a role; wood, stone and natural fibres evoke a connection to landscapes, while colours drawn from nature encourage relaxation.

Did you know that refuge spaces are based on principles from spatial and environmental psychology, particularly the prospect-refuge theory? They’re also part of the 14 biophilic design patterns created to promote feelings of safety and comfort.

Reconnecting with our origins through design

The prospect and refuge theory helps explain why certain environments feel intuitively right. It reminds us that we evolved in landscapes with distant views and nearby shelters. Neuroscience confirms that our brains still respond to these conditions, and empirical research shows that spaces combining openness and shelter reduce stress, improve mood and even speed up healing. Meta‑analyses highlight preferences for openness and moderate complexity, while field studies reveal that open‑protected sites are most appealing. Taken together, the evidence supports the prospect‑refuge design theory as a cornerstone of biophilic design.

Incorporating these patterns doesn’t require replicating savannas indoors. Simple interventions, adding a window seat overlooking a garden, arranging desks to face distant views, creating a cozy reading nook or curving a hallway, honor our evolutionary needs. By embracing the prospect and refuge theory alongside mystery and biophilic cues, designers can craft homes and workplaces that nurture creativity, reduce anxiety and reconnect us with the rhythms of the natural world.

Conclusion

Biophilic design taps into deep evolutionary instincts. The prospect and refuge theory encapsulates our dual desire to see ahead and to feel protected. Adding elements of mystery and natural complexity completes the picture, offering spaces that engage curiosity and support mental health. By integrating these patterns into interior design, we not only beautify our environments but also foster well‑being. Research shows that open views and protective nooks lower blood pressure, heart rate and cortisol, improve mood and cognitive performance, and even shorten hospital stays. As urbanization accelerates and digital distractions grow, reconnecting with our biophilic heritage through thoughtful design will be essential for maintaining health and happiness.

FAQ – Questions & answers about prospect and refuge theory

What is the prospect and refuge theory in interior design?

The Prospect and Refuge Theory explains how humans instinctively seek spaces that offer both a clear view (prospect) and a sense of safety or shelter (refuge). In interior design, this translates into layouts that balance openness with cozy, protected zones, aligning perfectly with biophilic design principles to enhance comfort and mental well-being.

Why does the prospect and refuge theory matter in biophilic design?

Because the theory mirrors our evolutionary instincts. Environments that offer expansive views (prospect) and secure nooks (refuge) resonate with how humans adapted in nature for survival. Integrating these into design helps reduce stress, increase focus, and promote emotional security, core goals of biophilic design.

Can you give examples of prospect and refuge in modern architecture?

Absolutely. Floor-to-ceiling windows overlooking landscapes offer prospect, while window seats, reading nooks, or alcoves provide refuge. The Fallingwater house by Frank Lloyd Wright and Bosco Verticale in Milan are iconic examples of architecture blending openness and shelter through biophilic and prospect and refuge design theory.

How does prospect and refuge theory impact workplace design?

Workspaces that incorporate this theory improve employee well-being and productivity. Open-plan areas with access to natural views (prospect) combined with private booths or green corners (refuge) cater to both focus and relaxation. Studies show that such biophilic design strategies can boost creativity by up to 15% and reduce stress-related absenteeism.

What role does mystery play in biophilic and refuge design?

Mystery is a powerful part of the prospect and refuge design theory. Curved pathways, partially obscured views, or filtered light create curiosity and encourage exploration. This aligns with biophilia’s focus on sensory richness and engagement, elements proven to elevate mood and cognitive function.

Is there scientific evidence supporting the use of prospect and refuge theory in interior design?

Yes. Research from the Human Spaces report and Terrapin Bright Green’s 14 Patterns of Biophilic Design confirms that environments aligned with our evolutionary preferences, like those outlined in prospect and refuge theory, can improve mental health, productivity, and our connection to place. Read more in this global report on biophilic design.

14 Comments